Workshops

Fundamentals of Finance for Company Directors

Online Workshop

Technical Knowledge & Skills CPD

Learn more

In this thought leadership article Economist Jim Power looks at geo-political uncertainty, the resilience of the Irish economy, and the upcoming Budget.

This time last year we were contemplating the possibility of another Trump presidency, but I am not sure how many believed it was really going to happen. In the event it did, and it is not an exaggeration to suggest that the first 8 months of his second presidency have been quite dramatic, with volatility and a total lack of predictability the defining characteristics. For business planning, uncertainty is a significant enemy and unfortunately, we have had it in abundance.

Of most relevance to businesses in Ireland, and particularly those that engage in international trade, is the attitude of President Trump to free trade and tariffs. He does not like the former but loves the latter.

In January, Trump stated that "I always say tariff is the most beautiful word to me in the dictionary," and this long-held admiration for tariffs has guided his every action since January. There have been so many tariff announcements since then that it is impossible to keep up, but the following are the most pertinent from an EU and Irish perspective.

On April 2nd we were treated to the Rose Garden tariff debacle or ‘liberation day’ with dramatic tariffs announced for every country the US trades with, and even some with which it does not trade. Following a very justifiable negative market reaction, he suspended those tariffs a week later for 90 days.

Then in late July, the EU and the US reached a framework agreement on the future trading relationship on a golf course in Scotland. It was a verbal agreement that lacked rigour and detail. The proposal was that from 7th August there would be a general 15 per cent tariff on most EU exports to the US, which is now happening. This was initially thought to apply to pharmaceutical imports from the EU, but this subsequently became less certain.

Shortly after the agreement was reached in Scotland, President Trump stated that initially there would be a small tariff on pharmaceuticals (15 per cent), but that within 18 months it would go to 150 per cent, and then to 250 per cent, because the US wants pharmaceuticals to be manufactured in the US. Then on August 21st in the framework document the US confirmed that it ‘intends’ to make sure that any future tariffs on pharmaceutical and semiconductor imports from the EU would be capped at 15 per cent.

Despite the trade framework that agreed, there is still a degree of uncertainty, not least the Section 232 investigation. In any event, a general 15 per cent tariff is not a good outcome for the EU, but Ireland is particularly exposed given its high dependence on the US export market. Some suggest that the deal that has been agreed brings more certainty and predictability, but this cannot be taken as given, such is the unpredictable nature of the US President.

Despite the threats to global trade, the global economy is doing OK. In the second quarter of 2025, GDP in the Euro Zone was1.4 per higher than a year earlier, and UK GDP was 1.2 per cent higher. While both growth rates are modest, they are still stronger than might have been expected. The US delivered annualised growth of 3.3 per cent in the second quarter. As always, the US economy continues to outperform the Euro Zone and the UK, but growth everywhere is less than stellar.

The ECB cut interest rates eight times between June 2024 and June 2025, taking official rates down to the lowest level since November 2022. The ECB is now in wait-and-see mode and will be watching data for future direction. ECB, interest rates are now likely to be at or close to the bottom of the easing cycle. A big concern for financial market stability is the way the administration is interfering aggressively with the independence of the Federal Reserve.

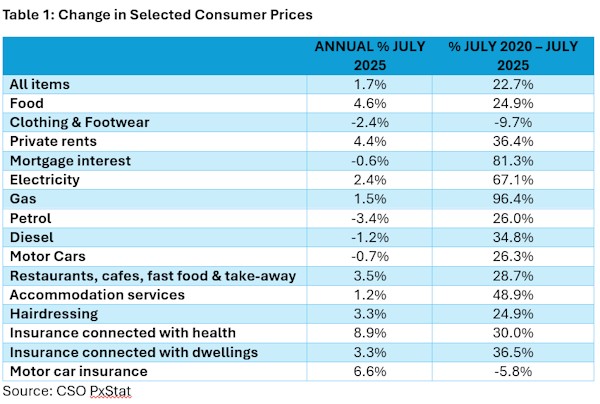

Despite the uncertainty, the Irish economy has continued to perform strongly on most metrics, but economic data in Ireland and other countries has been distorted by the front-loading of activity ahead of tariffs. A snapshot of Irish data shows:

Budget 2026, which will be delivered on 7th October, is the most consequential budget in a while. There is now an existential threat to the Irish economic model from the changed global geo-political context; national competitiveness is under considerable pressure; and the electorate has become accustomed to populist give-away budgets as manifested in a number of poorly targeted cost-of-living and other measures.

A budget package of €9.4 billion has been outlined by the department of Finance, with a net tax package of €1.5 billion, and an expenditure package of €7.9 billion. If the Government delivers the promised 9 per cent VAT rate for the food element of the hospitality sector, this could use up €580 million of the €1.5 billion tax package, leaving little room for personal tax concessions. The expenditure package will be comprised of current expenditure increases of €5.9 billion or almost 75 per cent of the total; and capital spending of €2 billion.

There was not a lot of detail in relation to economic assumptions in the Summer Economic Statement (SES) in July. The Department of Finance is projecting growth of 2 per cent in Modified Domestic Demand (MDD) in 2025, down from its forecast of 2.5 per cent in April, and 2.9 per cent in Budget 2025 last October. For 2026, MDD is projected to grow by 1.8 per cent, down from 2.8 per cent in April, and 3 per cent in Budget 2025. There is an ongoing gradual downward assessment of Ireland’s economic projections, which seems logical in the context of Trump-induced uncertainty.

Personally, I am cautiously optimistic about Ireland’s short-term economic prospects, but there are considerable longer-term risks and concerns. Housing, demographics, climate change, energy, water, and the efficient delivery of public services such as health and education warrant more attention. Government must adopt a longer-term strategic approach to addressing these issues and move away from the short-term focus that has dominated management of the public finances in recent years. The delivery of the national roads programme in the 1990s was the last time we saw genuine long-term strategic thinking from Government. We now have no choice other than to pursue more mature political decision making.

This article is the view of the author and does not necessarily reflect IoD Ireland’s policy or position.